But of course it hasn’t always

been. It was at best an ideal to be

strived toward but not always achieved. One

extreme example is the infamous Scottsboro Boys case. It came to the Supreme Court a few times,

most famously in Powell

v. Alabama (1932). I’ll let the Supreme Court describe what

happened.

The record shows

that on the day when the offense is said to have been committed, these

defendants, together with a number of other negroes, were upon a freight train

on its way through Alabama. On the same train were seven white boys and the two

white girls. A fight took place between the negroes and the white boys, in the

course of which the white boys, with the exception of one named Gilley, were

thrown off the train. A message was sent ahead, reporting the fight and asking

that every negro be gotten off the train. The participants in the fight, and

the two girls, were in an open gondola car. The two girls testified that each

of them was assaulted by six different negroes in turn, and they identified the

seven defendants as having been among the number. None of the white boys was

called to testify, with the exception of Gilley, who was called in rebuttal.

Before the train

reached Scottsboro, Alabama, a sheriff's posse seized the defendants and two

other negroes. Both girls and the negroes then were taken to Scottsboro, the

county seat. Word of their coming and of the alleged assault had preceded them,

and they were met at Scottsboro by a large crowd. It does not sufficiently

appear that the defendants were seriously threatened with, or that they were

actually in danger of mob violence; but it does appear that the attitude of the

community was one of great hostility. The sheriff thought it necessary to call

for the militia to assist in safeguarding the prisoners. Chief Justice Anderson

pointed out in his opinion that every step taken from the arrest and

arraignment to the sentence was accompanied by the military. Soldiers took the

defendants to Gadsden for safekeeping, brought them back to Scottsboro for

arraignment, returned them to Gadsden for safekeeping while awaiting trial,

escorted them to Scottsboro for trial a few days later, and guarded the court

house and grounds at every stage of the proceedings. It is perfectly apparent

that the proceedings, from beginning to end, took place in an atmosphere of

tense, hostile and excited public sentiment. During the entire time, the

defendants were closely confined or were under military guard. The record does

not disclose their ages, except that one of them was nineteen; but the record

clearly indicates that most, if not all, of them were youthful, and they are

constantly referred to as "the boys." They were ignorant and

illiterate. All of them were residents of other states, where alone members of

their families or friends resided.

However guilty

defendants, upon due inquiry, might prove to have been, they were, until

convicted, presumed to be innocent. It was the duty of the court having their

cases in charge to see that they were denied no necessary incident of a fair

trial. With any error of the state court involving alleged contravention of the

state statutes or constitution we, of course, have nothing to do. The sole

inquiry which we are permitted to make is whether the federal Constitution was

contravened...; and as to that, we confine ourselves, as already suggested, to

the inquiry whether the defendants were in substance denied the right of

counsel, and if so, whether such denial infringes the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

First. The record

shows that immediately upon the return of the indictment defendants were arraigned

and pleaded not guilty. Apparently they were not asked whether they had, or

were able to employ, counsel, or wished to have counsel appointed; or whether

they had friends or relatives who might assist in that regard if communicated

with. That it would not have been an idle ceremony to have given the defendants

reasonable opportunity to communicate with their families and endeavor to

obtain counsel is demonstrated by the fact that, very soon after conviction,

able counsel appeared in their behalf. This was pointed out by Chief Justice

Anderson in the course of his dissenting opinion. "They were

non-residents," he said, "and had little time or opportunity to get

in touch with their families and friends who were scattered throughout two other

states, and time has demonstrated 53*53 that they could or would have been

represented by able counsel had a better opportunity been given by a reasonable

delay in the trial of the cases, judging from the number and activity of

counsel that appeared immediately or shortly after their conviction."

It is hardly

necessary to say that, the right to counsel being conceded, a defendant should

be afforded a fair opportunity to secure counsel of his own choice. Not only

was that not done here, but such designation of counsel as was attempted was

either so indefinite or so close upon the trial as to amount to a denial of

effective and substantial aid in that regard.

In short the Supreme Court decided

that the right to be represented by counsel was guaranteed by the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in state proceedings (it was already explicitly

provided in Federal cases) and that the Scottboro boys had been denied this

right to counsel. Of course this was

only the beginning of their trip through hell, and their lives ended up ever

after ruined as this

site indicated. It is worth taking a

moment to read it.

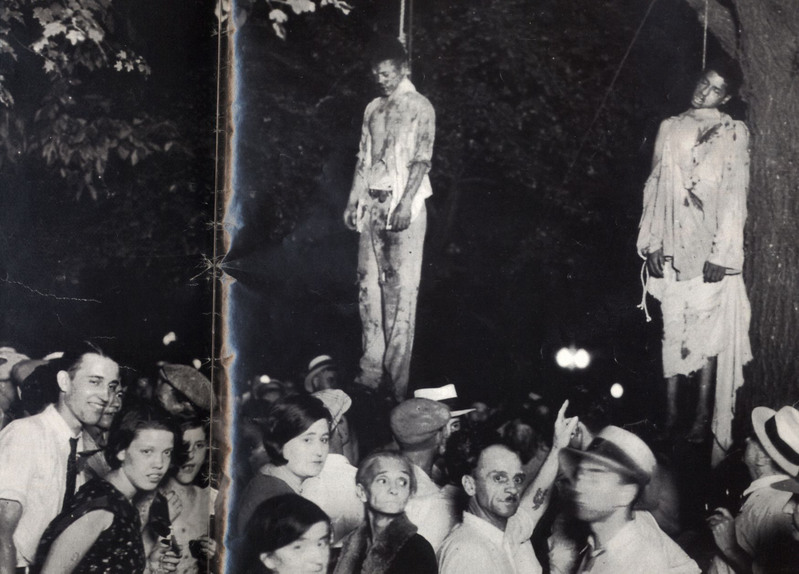

These young men were

profiled. They fit what the community

thought was a familiar narrative, filled with images such as on the left.

These young men were

profiled. They fit what the community

thought was a familiar narrative, filled with images such as on the left.

That is from Birth of a Nation, where a drooling black man (depicted by a white

man in “blackface” make up), attempts to rape a white woman. It was believed by racist whites that all or

most black men wanted to rape white women for various reasons, so when the

accusation was made, most of the white folks were half convinced it was true

just upon hearing the accusation—no evidence required.

This is not to say that no black

man in the 1930’s or earlier ever raped a white woman in the South. But the prejudice was so high that you couldn’t

trust a jury to discern accurately between the guilty and the innocent, or at

least those who are not proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

I think when it comes to

overcoming prejudice by society there are three stages of how a group is

treated in popular media. The first is vilification. The disfavored group is depicted as the devil

incarnate. Then, if people start to

rethink their prejudices, they go the opposite way: the rolls are

reversed. So for a long time in movies

every black man depicted was a paragon of virtue, handsome well educated, and

so on. Think of Sidney Poitier’s most

famous roles. And if it was a movie in which

someone needed to die heroically, there was a fair chance it would be the black

guy, such as was the case

in The Dirty Dozen. And then at some point people just start

treating that group as anyone else. They

might be heroes, villains or anywhere in between, just like anyone.

So there is a time where the

stereotypes were reversed. In the 1930’s,

black men were stereotyped as wanting to rape white women. But when Susan Estrich reported that she had

been raped by a black man, she found herself facing a new steteotype, that of a

white woman falsely accusing a black man of rape. In her autobiographical writings (read by me years

ago), she reported that the authorities didn’t take her seriously precisely

because they thought it fit into that template.

I don’t know if Susan Estrich was actually raped. I lean toward yes, but I haven’t heard a

thing out of the accused so I won’t draw any conclusions. But if she was raped, and she couldn’t get

justice, it was because she was paying the price for the misbehavior of women

who came before her. Naturally that

cannot reasonably be called justice.

This was the inverse, of course,

of what happened when white men raped black women. Of course it was always illegal to rape

regardless of color, but in the days of slavery those laws were pretty meaningless. Even if you had a prosecutor interested in

prosecution, you often had insurmountable boundaries to evidence. For instance, many states would not allow a

black person to testify against a white person at all, or only with another

white person first testifying that the black person was trustworthy. And even then you had to worry about the jury

refusing to prosecute just because they didn’t want to punish a white man for

harming a black woman. So while it was

technically illegal for a white man to rape a black woman, back then a white

man had little fear that he would be punished.

And thus black women were victimized.

So a few years back, in North

Carolina, we saw another reversal of stereotypes in the Duke Lacrosse case. Much like the Scottsboro boys, we had a doubtful

accusation of interracial gang rape, and too many people started fitting it

into historical templates. Too many

people intoned that “historically white men had victimized black women with

impunity.” That was true, of course, but

it had no bearing on this case with these facts. In too many people’s minds, the stereotype of

the rapine white men, seeking to pray on a black woman (combined with

stereotypes of rapist jocks) had become so powerful that it created such a

groundswell of political pressure to prosecute these men that Nifong famously

withheld exculpatory evidence and lost his license to practice law over it.

And so we come to the Zimmerman

trial, and history repeated itself, only at times it seemed more like

farce. The template was immediately set:

a redneck white guy hunted down and murdered an innocent black man and was let

off the hook by the “good old boys” in the police. And there can be no doubt that this sort of

thing happened in the past, but that has no bearing on what happened in this

case.

Indeed, the Zimmerman case never

fit the template at all. Zimmerman is

not a white man by any reasonable definition.

He self-identifies himself as Hispanic, and he

is even partially black. Indeed, he

is as black as Herman Plessy of Plessy

v. Ferguson (1896) fame. And that taps into a deep thought I have

about racial classifications. To me the

only significance of race is the existence of racism. So for me the entire point of the inquiry of

what a “race” a person belongs to is whether it is likely to inspire

discrimination and from whom and on what basis.

If a white racist encounters George Zimmerman, he is not usually going

to see him as “one of their own.” But a

racist Hispanic might.

So the entire theory of a “good

old boys network” saving one of their own never made any sense. And while it is not impossible to hate one’s

own ancestry, the fact he is partially black makes it unlikely that he hates

black people.

But it became important, for some

reason, for the left to play out this racial morality play. “In the past, a white man could murder a black

man and get away with it, but not this

time,” seems to have been the thought.

And if the Zimmerman case didn’t fit into the template, if the square

peg is not fitting in the round hole, by

God, we will hammer it in. So Zimmerman’s

heritage was denied and this man who actually fought

for justice for a black man, was made out to be a racist, people falsely

accused him of calling Martin a f---king coon, and NBC

deceptively edited the 911 recording to make it sound like he thought being

black was inherently suspicious. They

created a national uproar until the politicians felt they had to put him on

trial, whether he deserved it or not.

They demoted officers who protested.

They just fired the state’s attorneys’ office information technology

director for

giving the defense required discovery.

And there are people threatening to riot if Zimmerman gets off.

The ugly reality is that people

have been so whipped up there is a real concern that he will die no matter what

happens in this case: shived in prison if he is convicted, or lynched on the

streets if he is set free. The singer/rapper

Speech from the band Arrested Development once sang about going back to

Tennessee where he “walk[ed] the roads my forefathers walked/Climbed the trees

my forefathers hung from.”

Perhaps when they go to hang

Zimmerman they can find one of those trees.

Or instead, like Speech, they might “ask those trees for all their

wisdom.” The spirits of their fallen

ancestors might tell those people that the lynchings done in the past were

wrong, and doing the same to another will not make it better.

As I said in the beginning of this,

there were two key questions. Who struck

first? And did George Zimmerman

reasonably believe that if he didn’t shoot, he would face death or great bodily

injury. There is literally only one

piece of evidence on the first question: Zimmerman’s word. If you think he is a liar you have no other evidence and no

reasonable jury could find he definitely threw the first punch. (Bear in mind my usual admonishment that

Martin might have been allowed to throw the first punch as self-defense.)

The evidence got slightly

stronger on the second question, but the greater weight of the evidence says

that Martin was straddling Zimmerman, that he had broken his nose—which in many

jurisdictions is a great

bodily harm and even where it is not, you are well on your way to such harm—and

he was still pounding on him even after he was told by Good to stop. It is only then that Zimmerman pulled out his

gun and shot the kid. Even if you don’t believe that happened, am I being

reasonable in believing that it happened?

If you say I am not, then you must agree that he should be acquitted,

too. And also the entire time this case

was germinating, I always gave the caveat: I haven’t seen the state’s entire

case. So I was always open to the

possibility of surprisingly powerful evidence that would prove Zimmerman's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. But it never came.

Well, the time for open-mindedness

has passed. It is time to close our

minds upon a correct conclusion. If you

want to think Zimmerman is probably guilty, I won’t argue too much with you, as

long as you recognize that there is a reasonable doubt as to his guilt. And plainly, there is.

But like Professor

Jacobson I have a bad feeling about this case. It shouldn’t result in a conviction. In fact, it shouldn’t have been brought. But I am afraid that a jury of only six

people might be swayed by fears of riots, by the media, by something other than

those cold hard facts and send a man who shouldn’t go to prison to prison and

possibly even to his death.

Or perhaps they will remember his

black professor, saying a friendly “Hi” to his former student and take it as

permission to set him free.

This is a test of our

system. Can justice truly be blind? Can justice be done without being swayed by demagoguery

and threats of riots? And if he should

be set free, will the public accept that it cannot exact by private violence in order to enforce hallucinated

“justice” on the streets? In other

words, have we progressed past this image on the right?

Or are we only going to change

the colors of the victims and the criminals?

And what wisdom would we get from the hanging trees on that subject?

This is the test of our system, and

hopefully we will pass.

---------------------------------------

Disclaimer:

I have accused some people,

particularly Brett Kimberlin, of

reprehensible conduct. In some cases, the conduct is even criminal. In all cases, the only justice I want is through the appropriate legal process—such

as the criminal justice system. I do not

want to see vigilante violence against any person or any threat of such

violence. This kind of conduct is

not only morally wrong, but it is counter-productive.

In the particular case of Brett

Kimberlin, I do not want you to even contact him. Do not call him. Do not write him a letter. Do not write him an email. Do not text-message him. Do not engage in any kind of directed

communication. I say this in part because

under Maryland law, that can quickly become harassment and I don’t want that to

happen to him.

And for that matter, don’t go on

his property. Don’t sneak around and try

to photograph him. Frankly try not to

even be within his field of vision. Your

behavior could quickly cross the line into harassment in that way too (not to

mention trespass and other concerns).

And do not contact his

organizations, either. And most of all, leave his family alone.

The only exception to all that is

that if you are reporting on this, there is of course nothing wrong with

contacting him for things like his official response to any stories you might

report. And even then if he tells you to

stop contacting him, obey that request. That

this is a key element in making out a harassment claim under Maryland law—that

a person asks you to stop and you refuse.

And let me say something

else. In my heart of hearts, I don’t

believe that any person supporting me has done any of the above. But if any of you have, stop it, and if you

haven’t don’t start.

Pray.

ReplyDelete